Game Over, Computer Won HydraulicSheep on chess.com

Back in the middle ages, as the burgeoning game of chess spread into Europe, it began to harbour a unique following. Against the surrounding squalor and sickness, the elegant precision of the chess board became a haven for all. And for those trapped by oppressive classism, the grandeur of ‘The Game of Kings’ harboured escapism in its very pieces. Its ‘easy to learn, hard to master’ nature came to define it. So much so that, even with the rise of machines and computing, many remained sure that chess excellence was a uniquely human skill (even proposed by Alan Turing as a form of Turing Test).

So, it is worth noting that plenty of modern adults have lived their entire lives in a world where this game no longer exists. Of course, chess is still played (and with continual community growth). But no longer does human tact demarcate the borders of its elite realm. The walls have been toppled; the ivory citadel has been razed. And, while some may argue that computers have enriched the game, the state of modern play leaves plenty to be desired.

Therefore, let us examine the cultural significance, modern dominance and threatening future of computers in chess.

The mythos of chess

I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists. Marcel Duchamp, French-American artist and chess player

Egyptian chess players Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Wikimedia Commons

Likely emerging in India, the game of chess spread outwards, captivating all the cultures it came across and evolving. In Persia and the Middle East, it assumed abstract pieces and allegorical meaning. In East Asia, it morphed into the chess-like games of Xiangqi and Shogi. And spreading into Europe by the Arabian and Byzantine empires, it was loved by many. Chess became a symbol of status through lavish boards and social metaphor.

However, these noble roots of chess, immortalised in its pieces, belie a rich history as a game of the people. Indeed, unlike the games of croquet and polo that accompany status, a game of chess is quick and cheap to play. Just as Euclid once remarked to Ptolemy 1st, ‘There is no royal road to geometry’; so too does status afford no privilege in chess. The early chess masters are not kings or princes but scholars — still well-off but less so.

Early chess masters ****Ruy Lopez** and **Leonardo da Cutro** face off in the Spanish court ** Luigi Mussini on Wikimedia Commons

And if we idealise this, we begin to see some allure in chess: The elegance of a game that, just for an instant, takes two people, places them eye to eye, and makes them equal in all but wit. And yes, people gambled on it and found great thrill in it but there is more to chess’ significance. For, to truly understand all that chess can be, it would be reductive to label it as a mere trifle or even a sport. No. For many, there is something beautiful in its tactful precision. A formless shroud that surrounds the world of chess. It is an air of magic. It is art.

Just like the mystical worlds of fine art and music, so too does chess have its own mythos. The tale of the barefoot Indian master outwitting the maharajah. The absent-minded intellectual who wins with a flourish. The smirking child who topples the greatest of men, offering their tiny hand as little compensation.

Prodigies

Samuel Reshevsky versus the World Kadel & Herbert, New York Times, Wikimedia Commons

Indeed, the idea of ‘the prodigy’ has become part of chess culture just as in music. As a game comprising high amounts of training, little limit to entry, and long-lasting careers, it follows that a few extra years of exposure might produce better players. Thus the chess prodigy was born.

- Some were trained up by their parents from a very early age. For instance, the Polgár sisters were introduced to chess early and rigorously, producing three of the best female chess players the world has ever known.

The chess-playing Polgár sisters R. Cottrell on Wikimedia Commons

- Other prodigies emerged as skilled players from merely their own fixation. Reportedly, chess greats Paul Morphy and José Capablanca were never explicitly taught the rules of chess and instead learned by watching their families play.

- And many of the world’s best players — including Magnus Carlsen, Fabiano Caruana etc.— enter the professional scene while still in their adolescence. Regardless of how they learnt, there is something truly wondrous about a young child winning at chess when in all other capacities they are limited. Thus a layer of mystique is added to the mythos of chess.

Symbolism

Interacting with this history, chess mastery has become an easy stand-in for intelligence in popular culture, serving two main purposes:

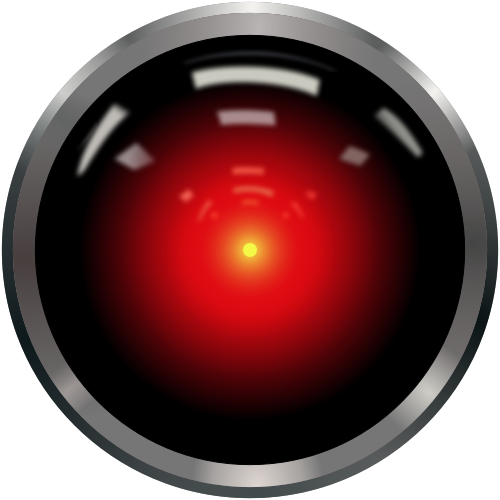

The ominous AI Hal-9000 (2001: A Space Odyssey) whose chess skill is immense Cryteria on Wikimedia Commons1.

- Highlighting the intelligence of a character or as reinforcing ‘intelligent’ filler.

- The film ‘Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows’ demonstrates Holmes’ sharp intellect by conquering his nemesis Moriarty at chess. Clearly writers Michelle and Kieran Mulroney decided chess was the most suitable game to best characterise one of history’s smartest fictional characters.

- More prominently, in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, chess adds extra depth to Ron Weasley’s character. By Ron’s quick grasping of what moves must be made, he is depicted as intelligent in a non-traditional fashion. Rather than chess ability aligning with academic smarts, it becomes a marker of talent in general.

- Framing computer intellect (particularly in an uncanny light)

- In the film WarGames, chess is just one of many capabilities of the dangerous artificial intelligence WOPR. Although a game is not played, chess was clearly deemed a fitting companion for the sinister machine.

A recreation of WOPR’s final words in WarGames HydraulicSheep*

And in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick’s depiction of AI Hal-9000 playing chess has similar connotations. By this, the AI’s sinister limitations were perfectly foreshadowed for viewers of the time. He enters a kind of uncanny valley that comes too close to human capacity while still falling short.

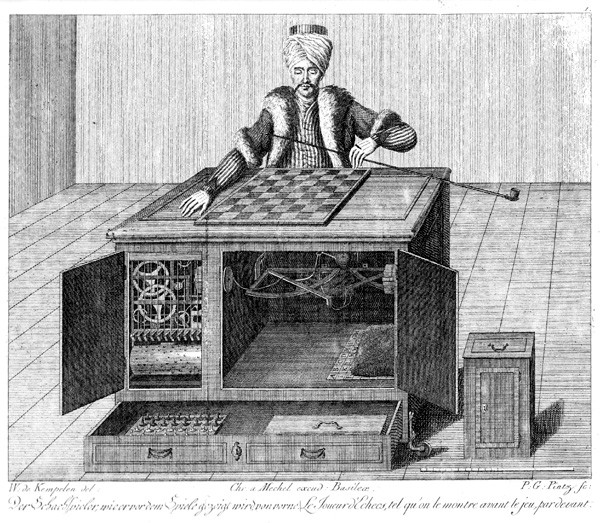

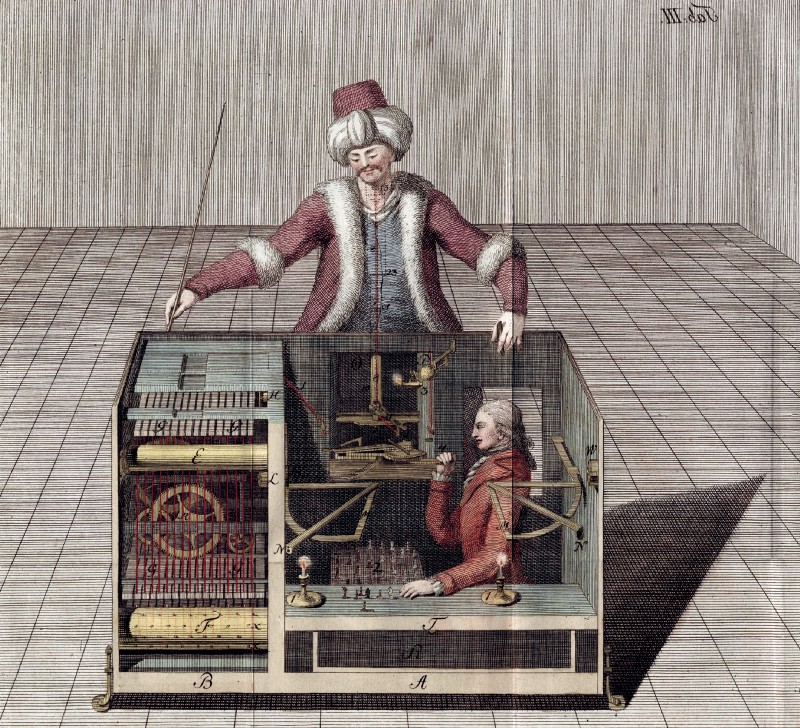

Mechanical Turk

The Mechanical Turk Karl Gottlieb von Windisch on Wikimedia Commons

So, considering the game’s sprawling culture, it is no wonder that the early chess machine, Mechanical Turk, caused quite a stir in the community. It — a mere machine — defeated player after player with ease. While some were struck with a horror resembling the Pythagoreans’ dismay at irrational numbers, the crowds came flocking with morbid curiosity. Could the complexity of chess be cast off by gears and clockwork?

Not yet.

The Turk, although fraudulent, mimicked the genuine article so well that, there was no true consensus on its nature. Although some were correct, others guessed incorrectly, and others still were convinced of its legitimacy. (“The Last of a Veteran Chess Player”, The Chess Monthly, January 1857)

Secrets of the Mechanical Turk Joseph Racknitz on Wikimedia Commons

And the crowds ate it up. Its tour of Europe was long-lived and attracted names from Paul I of Russia to Napoleon.

Although it lost some games, the appeal was its high skill-level which seemed impossible for a machine to achieve.

Finally, when its fraud was revealed, the sham of the Turk seemed only to bolster Chess’ pristine image. Suspicions were fulfilled and once again people felt reassured that the game’s revered status was secure. It and other imitations fell rapidly into obscurity.

Tackling Chess Artificially:

Personally, I rather look forward to a computer program winning the world chess championship. Humanity needs a lesson in humility. The Selfish Gene*, *Richard DawkinsAlongside this high-art of the chess world, mathematicians and scholars began to gradually chip away at its marble pedestal.

**As game theory developed, maths and chess began to collide **Roman Mager on Unsplash

Mathematical Attempts

As with many mathematical discoveries, a variety of general forays into chess paved the way for more rigorous approaches by future generations:

- Ernst Zermelo penned Zermelo’s theorem which started mathematically investigating chess.

- Mathematicians like John von Neumann laid the foundations of game theory. This area of mathematics deals with games using tools like game trees and payoff matrices. It would be crucial in tackling the immense complexity of chess.

- Claude Shannon estimated ‘The Shannon Number’ as a conservative lower bound for the complexity of chess’ game tree — the more possible games, the greater game tree complexity. The number, 10¹²⁰, is even far larger than the number of atoms in the entire universe. This set a clear barrier against brute force analysis and established that a more intelligent approach would be required.

According to the Shannon Number, there are more possible chess games than there are stars in the entire universe Scott Wylie on Flickr

And on top of these, attempts have been made towards ‘solving’ chess. In this case, ‘solving’ is a game theory term that refers to a game whose outcome (win, loss or draw) from any game state can be determined assuming optimal play. So, suffice to say, solving chess would significantly change our relationship with and approach to the game.

In other games, solutions have been successfully found.

- Tic Tac Toe is well known as solved.

- A few decades ago Connect 4 was solved

Optimal Tic-tac-toe moves for X player nneonneo on Wikimedia Commons

However, chess, despite receiving much mathematical attention, is one of few common games (Go included) that remains unsolved. Once again this stems from chess’ great complexity.

So, if it can’t be solved, it can’t be brute-forced and no mathematical hacks have been found, how do engines play chess?

Game Theory and Algorithms

Ultimately, it was not a great mathematical insight that advanced chess engines, but rather the application of computation towards game theory approaches.

There are three main aspects to this:

- The strategies used by traditional chess engines These utilise game theory to aim for traditional chess goals, just as a human might.

For example:

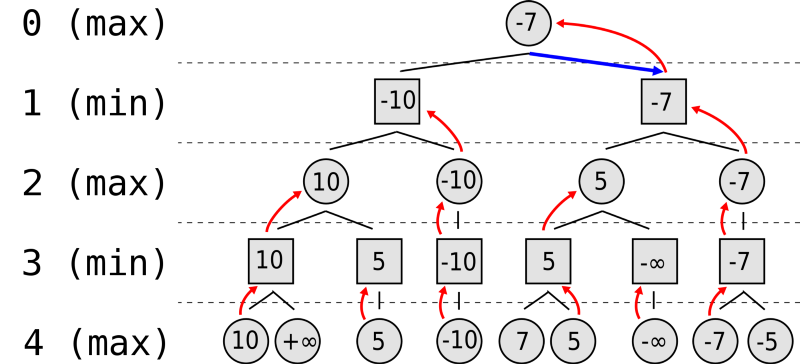

- Minimax This approach makes the move which will minimise the quality of the opponent’s best possible move.

Minimax Tree Diagram Nuno Nogueira on Wikimedia Commons*

Alpha Beta Pruning This is used with minimax to eliminate move trees which have been proven to be worse than other available moves

Alpha Beta Pruning in action Jez9999 on Wikimedia Commons

And these strategies evaluate the quality of positions via traditional chess goals like:

- Pieces being worth different amounts

- The value of a bishop pair

- Rooks on an open file.

Traditional Chess Piece Valuations Wikipedia2.

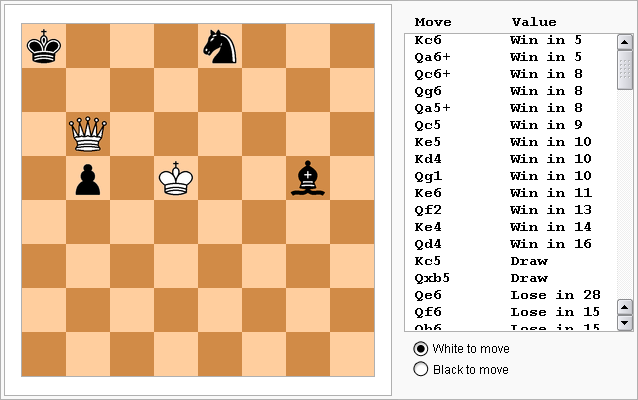

Tablebases and ‘knowledge’

As with rainbow tables in hash breaking, tablebases trade off computation time for storage space by saving openings and precalculated endgames. As the strategies listed above are quite probabilistic, this addition ensures that the correct decision is always made in solved situations.

Engame Tablebase with small number of pieces User:ZeroOne on Wikimedia Commons3.

Hardware

We musn’t neglect the significant effect of technological progress. With each incremental hardware improvement, as predicted by Moore’s Law, computational power increases. This allows for greater engine search depths and better play.

The engines triumph

Implementing all these methods on custom hardware, IBM’s Deep Blue played a series of matches against the then world champion, Garry Kasparov. Each match, as a series of 6 games, used standard tournament conditions with classical time controls. This traditional format made the engine’s wins a world first both in format and significance.

Deep Blue and Garry Kasparov Jim Gardner (left) and Owen Williams, The Kasparov Agency (right)*

In 1996, the first match was played. Although Kasparov emerged on top with a comfortable 4 points to Deep Blue’s 2, there was certainly something unnerving about the engine’s game 1 victory — a world first of its kind.

- So it is no wonder, only a year later, that Kasparov succumbed to the engine in the second match between the pair.

- Commentators remarked that Kasparov’s quality of play was worse than expected and he even levelled accusations of cheating against the engine. Given these circumstances, it is worth noting the psychological tensions at play: Kasparov with everything to lose and the engine with all to gain.

- Further, a pinch of luck reportedly tipped one game in the engine’s favour. Apparently Deep Blue’s opening tactic in the final, decisive, game may have only added to its tablebase that very morning.

Deep Blue stands triumphant Jim Gardner on Flickr

So, perhaps Kasparov could have won. But regardless, there was something truly symbolic and signigicant about how far computers had come as to hold their own with the world’s greatest chess mind of the day.

And at the time, Deep Blue’s win even seemed to indicate that computers could rival human intelligence, that they were something to “Be Afraid” of.

Modern Era

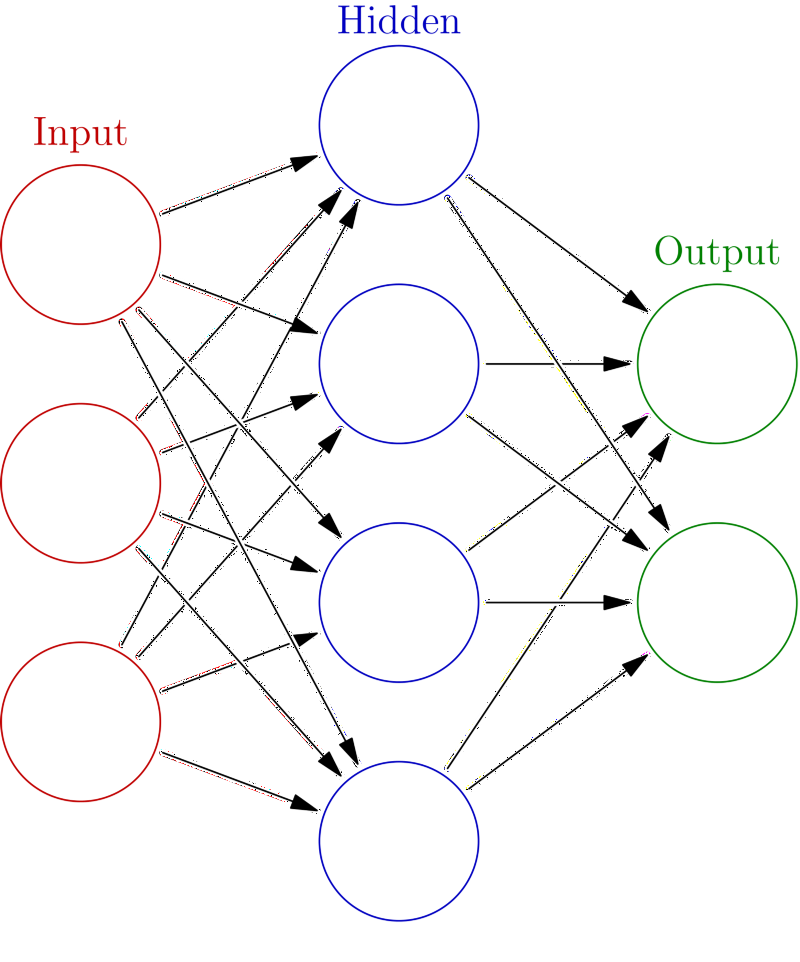

“The world is complex. That complexity is beautiful.” Computer Pioneer Ward Cunningham, “The Simplest Thing that Could Possibly Work : A Conversation with Ward Cunningham” Part V#### Machine Learning

Then along came AlphaZero. In one fell swoop, it outpaced humanity and even the reigning engine, Stockfish. Youtube commentators remarked at how strangely it played. How opaque was its method. How it played by rules we didn’t understand. Game after game it began strangely before always emerging ahead. Beauty and elegance gave way to shadow.

Machine-learning-based networks rely on opaque weights and biases rather than programmed chess principles to play Glosser.ca on Wikimedia Commons

Or did they?

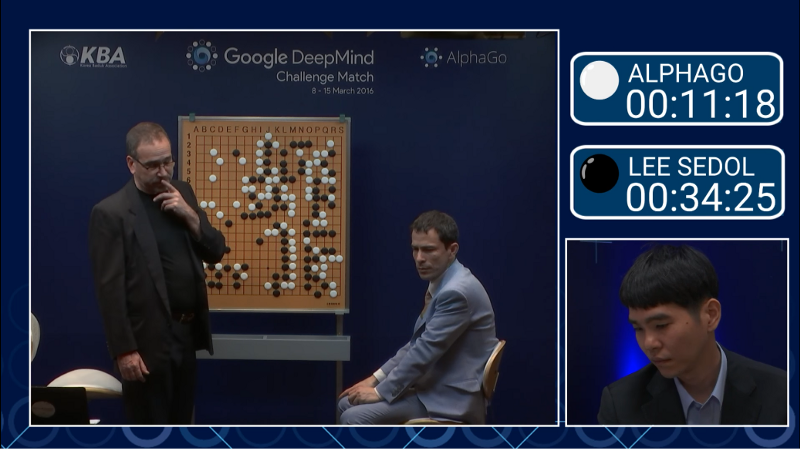

The game of Go had their own ‘Deep Blue’ moment a few years ago when DeepMind’s AlphaGo came up against reigning Go champion Lee Sedol. As much as Sedol despaired (and retired) upon realising the excellence of AlphaGo, fellow master Fan Hui described its play as “So beautiful”. And he has spent the last few months playing the bot and learning from it. Because maybe if we uncover how these bots tick, we can elevate our own understanding to new, loftier heights. Full understanding will come someday but there is no “royal road”.

Tense moment in AlphaGo’s first match against Go master Lee Sedol **Deepmind Youtube#### **The new depths of human skill

And this excellence has been developing in human chess for years. With the huge availability of traditional bots like Stockfish, it is easier than ever to train oneself against tough opponents; ‘If you can’t beat ’em, join ‘em’. While some have critiqued the record number of draws in the recent Chess World Championship and demanded new formats, this merely reflects the state of modern chess. With the help of engines, play has become so good that the top players are drawing more and more by the day. Maybe we need something like AlphaGo to imbue the game with fresh inspiration.

The 2018 World Chess Championship saw 12 successive draws between defending champion Magnus Carlsen and challenger Fabiano Caruana Author Pablo Martínez Rodríguez on Wikimedia Commons

To be fair, chess has been showing its faults for generations. Even past World Champion Bobby Fischer suggested the alternate format of Fischer random chess (where the orientation of back rank pieces is randomly chosen) to combat the importance of memorising opening books. In 2018, the World Chess Championship didn’t see a single win in twelve games and had to be resolved by the faster time control of ‘rapid’ chess. There is no doubt that these games were an immense test of ches skill but, at least on the surface, twelve successive draws are a little disappointing. Considering that analysts believe Carlsen had a better position in the last game and just held out for the tie-breaks, maybe we need new formats which encourage being bold. Just like in fencing where the idea of ‘priority’ encourages one fencer to attack, so too could chess demand more aggression from one player.

And yes, from the perspective of a game or a sport these plentiful draws and stale formats may be uninteresting. But returning to the essence of chess as an art-form, modern chess is more beautiful than ever. Each stab is deftly parried by the opponent in a dazzling show of thrust and counterthrust. Or instead a slow strategic positioning takes place where both sides vie for incremental advantage. Maybe it will end in a draw but the spectacle is there and it is beautiful.

Rising from the ashes

To find the fiery spirit of chess, we need look no further than its vibrant community which burns brighter than ever.

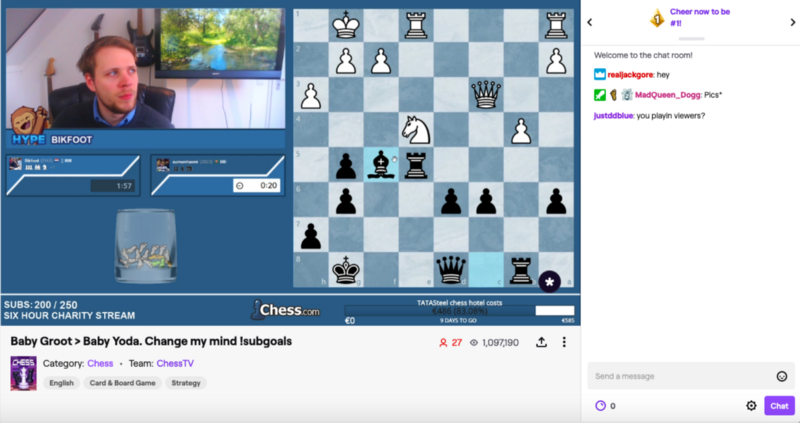

On Twitch, following the rise of video-game streaming, world class chess players broadcast online matches to thousands of viewers. Labelled as “Banter Blitz”, streamers bring out the fun and emotion involved in chess with viewer interaction, commentary and witticisms. This breaks away from the solemn atmosphere that has traditionally surrounded the game.

Banter Blitz streamer Bikfoot on twitch.tv Screenshot by HydraulicSheep of bikfoot’s stream

On Youtube, educators (such as agadmator and ChessNetwork) work tirelessly to dissect the endless torrent of grandmaster games while also trawling over historic material. Not only do these personalities entertain but they cut to the core takeaways from high-level chess.

And learning materials in general are easier to access than ever. Tools like engines, opening tablebases (long libraries of openings) and past game records are all freely available within a few clicks.

Even valuable access to opponents is available 24/7 through sites like lichess.org or failing that, an offline chess engine. No longer need you visit chess clubs or libraries; wherever you are in the world, at any time, you can play an opponent around your ability level.

Chess site ‘Lichess’ serves numerous chess tools to thousands of users Screenshot by HydraulicSheep of lichess.org

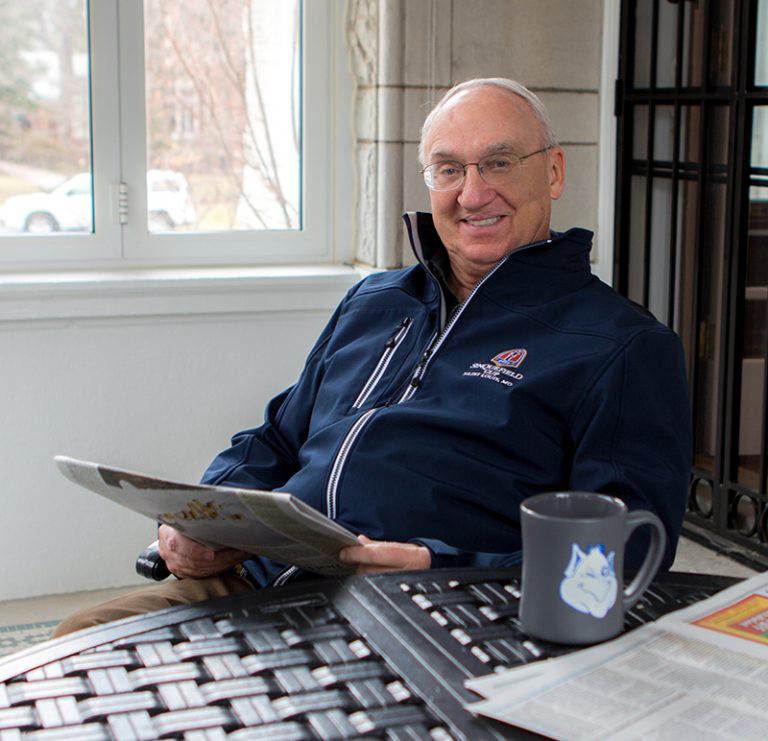

And perhaps best of all, a promising future lies ahead through the pîqued interest of sponsors and donors. Philanthropist Rex Sinquefield, having contributed “tens of millions” to chess ventures in the last few decades, is just one of many inspired donors paving the way for chess to flourish.

Philanthropist Rex Sinquefield. A generous chess supporter of chess development. rexsinquefield.com

Even the country of Armenia has backed chess as a valuable skill by adding the game to its national curriculum.

So, from the looks of things, the game of chess still has a long prosperous life to come: a life that plays into its rich history of accessibility, unity and joy.

Conclusion

“The beauty of chess is it can be whatever you want it to be. It transcends language, age, race, religion, politics, gender, and socioeconomic background. Whatever your circumstances, anyone can enjoy a good fight to the death over the chess board.” Simon Williams

The game of chess unites all: young and old alike Vlad Sargu on Unsplash

It is easy to see that chess has changed. To those who watch for artistry and human ingenuity, perhaps it is fading. But this shift has not made the game less culturally significant. Rather, it has grown. From Twitch to Youtube to TV to Pop Culture, chess is bigger than ever. 30 years ago a bright era ended but now another day is dawning.