The bustling forecourt of Yiwu Market. Haluk Comertel on Wikimedia Commons

In the Chinese city of Yiwu, situated nearly 250 km from Shanghai, the long halls of the ‘International Trade City’ stretch along the horizon. This single market, which is hailed by the World Bank as “the world’s largest small commodities market”, sold US$11 billion of goods in 2013. Of course, in more recent times the Internet, with giants like Alibaba and Amazon, has gained increasing relevance in sourcing the world’s small goods. And amidst the changed landscape of this area, it is through the journeys of these goods from factory to customer that we are able examine consumerism. To my mind, once these goods are produced, they undergo three main stages: Markets, Transport and Distributers. And so, to begin scrutinising modern consumer culture, let us travel to an import marketplace of many everyday goods: Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

Importer Markets:

Walking the halls

Tourist goods for various countries sold in Yiwu market. iamdanw on Wikimedia Commons

Picture this: In front of you, the corridor stretches endlessly. Behind you, the same. On either side, racks and racks of the same goods with only slight variations line the walls.

Stretching on for 5,500,500 square metres, this one small-goods market in Yiwu covers the area of nearly 800 soccer fields. Within its walls, any small, reasonably-priced object conceivable can be found. But this market isn’t one where you buy one shirt or one doorknob but thousands. Unlike the large malls familiar to US consumers, suppliers here try to woo large companies or importers who need copious quantities of exactly the right item — hence the size of the place. It’s a wonder that anyone can decide on anything with so much choice. But people try. When interviewed by CNN, photographer Richard John Seymour claimed that “I spent a total of four days constantly walking around Yiwu and wouldn’t say I got near to seeing all of the stalls.” I suppose one must wonder why people come and what the draw of this place is.

The variety at Yiwu is endless. From toys to flowers to doorknobs. Credit: Banalities on Flickr

For one, the scale certainly provides insight into the modern retail economy. The fact that this much variety is just sitting here, perpetually, and ready to be mass-produced at the whim of some businessman both inspires awe and evokes existential dread. The huge-scale supply chain machinery that frames our world seems impenetrable. And the opacity of such a fundamental system from a Western perspective verges on sickening. It doesn’t help that the raging trade war between the US and China is continually driving further wedges between our societies (not to mention the general unease caused by the Hong Kong protests).

The keys to Yiwu’s tale and this examination as a whole are complexity and scale; these have become attractions in their own right. Somehow these distribution centres transport visitors to another world, fulfilling a sort of wanderlust (with the end of viewing the depth of our human world rather than the environment around us). If you don’t believe me, take a look at Shenzhen.

The tech markets of Shenzhen

Electronics Market at Chegongmiao, Shenzhen. Jirka Matousek on Flickr

As with the small goods of Yiwu, if we turn our gaze a little further east, the electronics markets here attract importers seeking technical components. One of the most famous, the 10-floor-tall SEG Electronic Market, has attracted media attention online with almost Cyberpunk-esque appeal. Although similar in role to Yiwu, the proximity of these to major tourist centres as well as the emerging ‘Silicon-Valley-like’ culture have brought Shenzhen onto the world stage. And the tourists have only come flocking in, eager to gaze into the chasm of our world’s inner workings.

However, there seems to be more than that. The appeal of these markets cannot be simply that of curiosity — there are plenty of breathtaking sights in China. Rather, they must have a deeper appeal. Similar to an oasis in a desert, there is something culturally familiar about these markets. The consumer experience provides familiar cues in what is, for many Western tourists, a culture that they don’t fully understand. Just as Marco Polo travelled into foreign lands and was guided by his mercantile endeavours, so too does the idea of consumerism tie together the disparate cultures of our modern world with its warm familiarity.

On the internet

Logo of online supplier Alibaba. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

With the advent of the internet and the aforementioned inaccessibility of these markets, online suppliers such as Alibaba have emerged as a gateway into this world. Just like the Shenzhen markets, there is room for both bulk sourcing (through Alibaba itself) and direct purchases through AliExpress. And the value of this gateway into the bowels of our supply chains cannot be understated considering its great commercial success on the New York Stock Exchange (with the biggest US IPO in history). However, this is not to say that the site is accessible. In all my experience with AliExpress, the whole process has been clouded with a creeping unease that it’s hard to quite put my finger on. Perhaps issues like product keyword spam, suspicious reviews in many different languages and the typically bleak shipping options all contribute to this.

The keyword spam and coupons familiar to the AliExpress experience

So, realistically, this sits closer to Yiwu and Shenzhen (as a supplier marketplace), than it does to online retailers built with customer focus in mind.

What distinguishes these end retailers like Amazon is not more variety. Instead, as well as Amazon’s logistics network which slashes delivery times, you pay them for assurances of quality, consumer protections and approachability (as will be discussed later). And as much as Alibaba’s customer service is well-reputed, it still seems to fall short of that mass-market direct to consumer appeal in the US.

It is certainly worth noting that these points of distribution have attracted widespread interest — they are by nature places for buying and selling — unlike the factories manufacturing these goods. Whereas the conduct of factories in the US has been illuminated by unions and bureaucracy, many other manufacturers of the modern world remain shrouded in mystery. We’ve all seen the media outrage at Foxconn and countless reports of oppressive worker conditions in sweatshops across large swathes of South-East Asia. Apart from what we hear in the news, there is no ‘in’ to this world. The sprawling markets of their products are as close as us plebeians can get.

The Rana Plaza garment factory collapse in Bangladesh Credit: rijans on Flickr###

Transport Processes:

The machinery

Modern Port with machinery and standardised containers. Image by Jason Goh from Pixabay

To facilitate the sheer size of supply that must reach customers across the globe, it is fitting that the machinery with which we transport goods is equally massive. Of course, the cargo ships themselves have grown to parallel the increase in scale: once we had small sailing trade ships which became the sizeable cargo liners in use today. Likewise, the port machinery has grown to favour scalability with standard cargo container sizes and dock machinery built to handle these.

Even more admirable is the international standardisation that equals the physical infrastructure in complexity. The international collaboration and agreement across conflicts and borders to facilitate this is in itself a thing of scale. And as the wheel of progress pushes on, so too, do ports.

Lately, eyes have turned towards utilising the Internet of Things to force up capacity. These aim to remove another imperfection in the transport system — the human element. Why have hundreds of humans acting with imprecision when one computerised system could control it all? It’s the same idea as total driving automation but on a smaller scale. If everyone drives the same self-driving car and there are no pedestrians/cyclists then the system works near perfectly. If all the port machines are automated by the same system and there are no human interlopers, the port can operate at near peak efficiency.

Smart, data-collecting container 42 as part of the Port of Rotterdam’s smart port initiative. Credit: Photos: Grant Pinkney (Kramer) on portofrotterdam.com

And across global shipping lanes, maximal efficiency is no less enabled.

Global shipping super-highways

The massive Panama Canal in operation. Credit: Roger W on Flickr

Apart from the vital codes governing international shipping lanes, two large pieces of infrastructure — the Suez and Panama canals — enable the huge scale of this economic operation. So much so that these canals have become important standards for designing ships, lending their names to the Panamax and Suezmax classes. Of course, the sheer effort involved in moving such huge mounds of earth is impressive. But, considering the reality of physically splitting continents to unite our world, one ought to recognise the momentous sequence of events that has brought goods across the oceans that divide us.

Panamax Container ship. This class of ships meet the length, width and height specifications of the Panama Canal. Credit: Wikimedia Commons###

End Retailers:

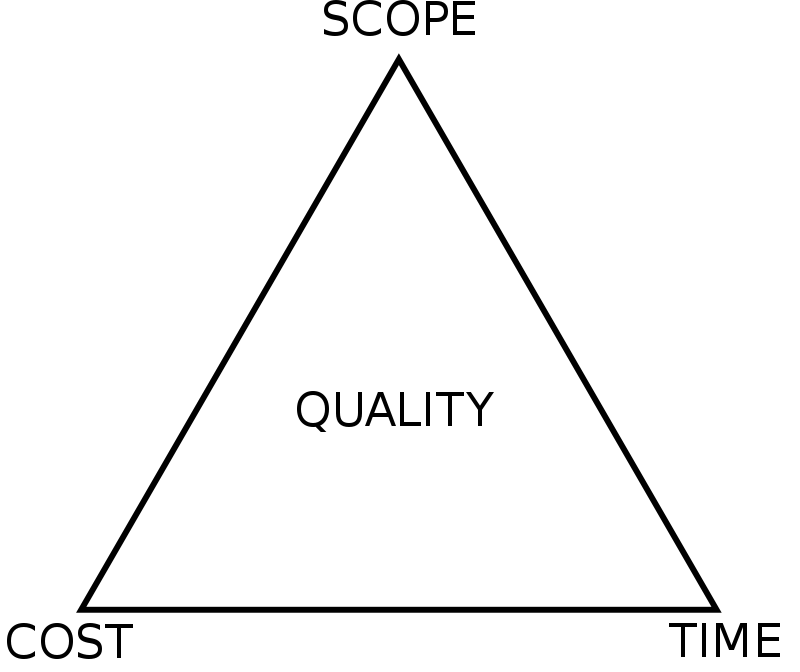

As we approach the end of this chain where goods reach customers, a fundamental principle governing all sellers of goods begins to emerge. This is that price, variety and accessibility all constrain one another. Similar to the “Project Management Triangle” where Cost, Time and Scope cannot all be maximised and much be balanced according to the project’s specifications.

The Project Management Triangle which bears similar constraints to global supply chains

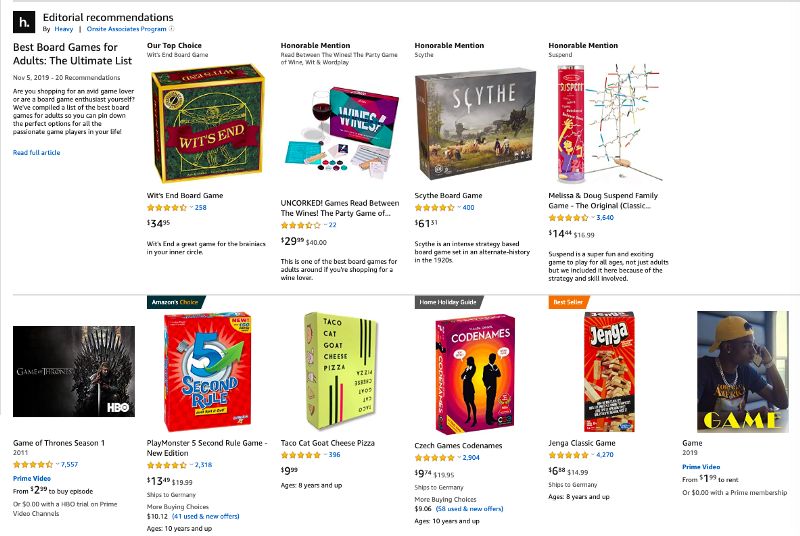

For instance, Amazon’s very brand centres around the idea of mass diversity. Just like the millions of crates transported across the ocean and the thousands of small items in Yiwu, at this terminal stage of the supply chain, the diversity shines through. However, unlike the maze-like alleys of Alibaba, Amazon seems far more approachable to the average American. Shipping times are well-defined. Familiar brands surround. Reviews generally make sense. But in accomplishing this, a careful eye has been turned towards curating the site so some unadulterated variety has been sacrificed for accessibility.

For the same search, Amazon provides best sellers, curated editorial suggestions and clear age recommendations.

And of course at this same level, there are familiar traditional retailers who each strike their own balance with the aforementioned constraints.

So, there you have it. Max diversity to minimum. Low Price to High. High opacity to high accessibility.

However, 200 years ago these same ideas applied yet capacity was still lower.

How have we pushed against these constraints to maximise all of the variables?

Three words.

Economies of Scale

Underlining all the observations so far is the grandiose scale and insurmountability of the involved systems. Although this huge scale may seem like a challenge in itself, it rather serves as an impetus. For each small advancement in technology, the resulting increase in economic scale nurtures itself. Processes become more efficient. Technology investment is encouraged. Scale begets more scale.

In a way, increases in scale act in snowball fashion cascading towards more scale. Credit: Kaymar Adl on Wikimedia Commons

This concept helps to explain two key observations of the systems above:

Firstly, regarding the huge variety of goods. The huge diversity allows for the diversity itself. It means that at markets, although stocking a great diversity of samples is taxing, importers are more likely to find a suitable match which they will purchase on a bulk scale to outweigh the maintenance costs.

Secondly, the massive quantities which these very supply chains have built themselves up to handle make access to transport and supply options more cheaply accessible. The path is well-trodden so the necessary infrastructure and knowledge is firmly in place.

And this economic truth, although beneficial to the economic growth of our modern wealth, has perhaps encouraged corruption of our consumer culture.

Throwaway Culture

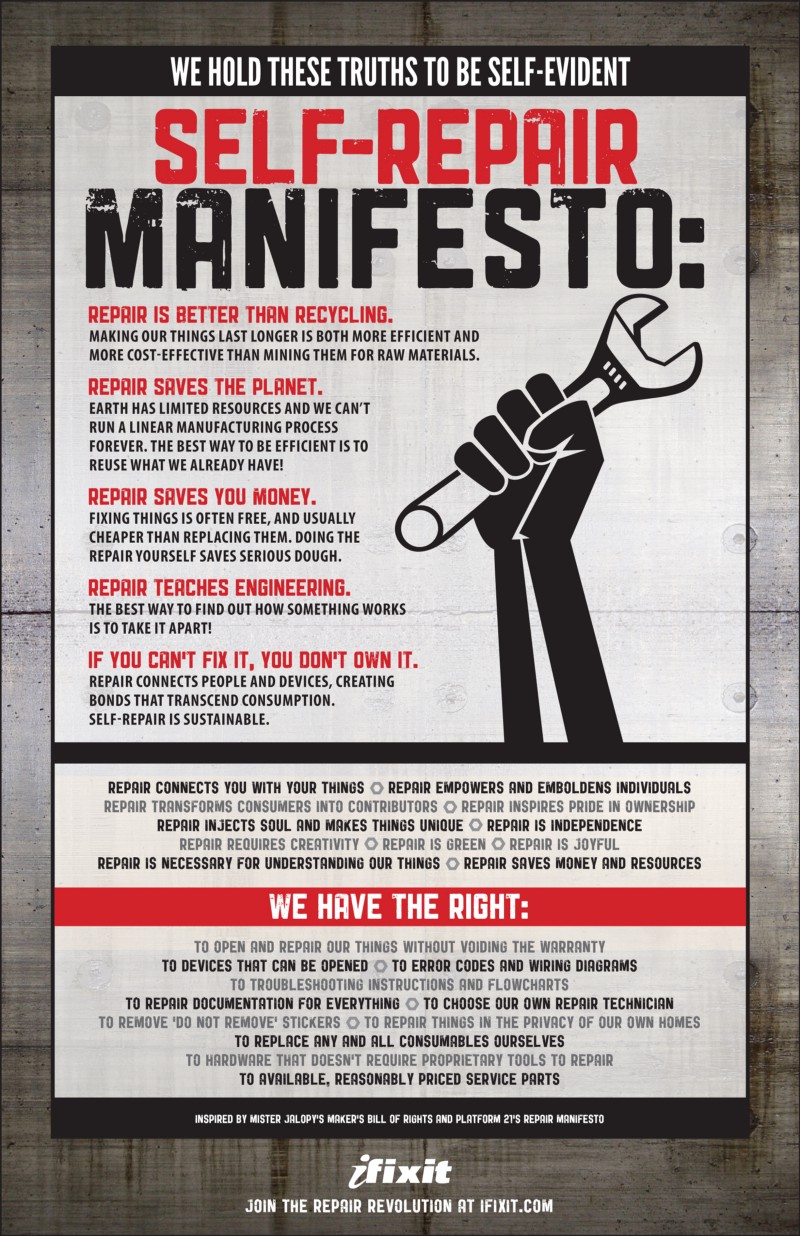

For groups like iFixit.com, the self-repair movement has become an important weapon against a throwaway society. Credit: Dunk on Flickr

Our modern tendency to maximise variety (as explained above) necessarily reduces the connection we have to individual items. And with this sheer variety, companies must compete harder to win over consumers who are far more likely than ever to be struck with decision paralysis, only driving prices down further.

This is the reason that before the acceleration of these mass supply chains, you would be much more likely to repair your television or refrigerator than replace it. Now prices are competitive enough that buying a replacement entails less hassle. And isn’t there something inherently satisfying about purchasing something new and pristine? This is embodied in the very concept of ‘retail therapy’. Many consumers simply take a path of least resistance so the tendency to treat items in throwaway fashion has become ingrained in our culture.

As well as the lower hassle of replacement, for some ‘retail therapy’ has a soothing allure. Credit: Image by gonghuimin468 from Pixabay

To my eye, a good indicator of this is found in recent writing from the Pope. Of all the pressing moral quandaries and scandals involving the Church, he devoted his first papal encyclical (a treatise on a certain topic from a religious standpoint) to this very idea. In the piece ‘Laudato Si’, he critiques the squandering of our planet’s resources through a culture of consumers always seeking the next thing. The fact that the leader of one of the world’s largest religions devotes his attention to this is rather telling.

The Pope’s comments as a busy leader of a global faith somewhat legitimise the issue of consumerism Credit: Jefferey Bruno on Wikimedia Commons

Of course, all this ties into the images we have all seen of plastic pollution, over-consumption of natural resources and animal extinction.

Sure, this is nothing new. Overfishing has always been a reality and the Industrial Revolution greatly harmed surrounding environments. Even the crew accompanying Charles Darwin on his voyages couldn’t stop themselves from eating all the delicious giant tortoises before their vital evolutionary evidence could be returned to Britain. But these were merely a few people indulging a little to stave off the darkness in their bleak world.

The effects of over-consuming are made very visible in our world via deforestation. Credit: Dikshajhingan on Wikimedia Commons In modern times, consumerism has become ingrained in our culture. At every stage in the supply chain, scale and quantity are emphasised. The cheapness of goods and the sheer abundance of them make it nye on impossible to effect change as a collective.

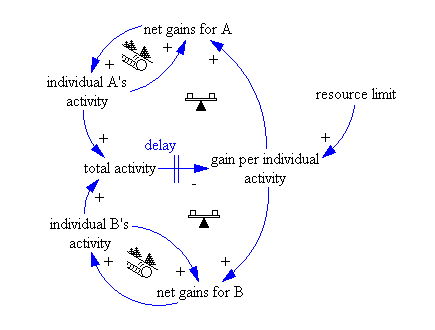

Perhaps this calls to mind the the Tragedy of the Commons. Although exploiting our natural world will harm the entire human race as a whole, there will always be someone who will purchase the cheap goods for some short-term gain.

Diagram explaining The Tragedy of the Commons Credit: B Jana on Wikimedia Commons

And, yes. This mentality is being increasingly denounced in the form of plastic bag bans and the advent of metal straws. However, this doesn’t change the fact that emerging economies have become reliant on these cheaply available, disposable goods. Further, I think we have all questioned the true efficacy of these small-scale efforts like replacing plastic straws. To me it seems like an easy way out. A way to address our nagging guilt without actually changing our damaging ways. A way to justify, not remedy, this throwaway culture.

It seems hard to believe that a simple straw will have a noticeable impact… Credit: Sue Telford from Pixabay

Thus, there is something deeply troubling about our society’s consumerism.

We purchase the newest phone model or technology must-have.

We take mediocre care of it so that the screen cracks or it suffers water damage.

We purchase a new one because it’s easier and more satisfying than repairing it.

We inhabit a planet whose finite nature is immortalised in the forests we demolish and the rivers we suck dry.

As residents in such a vulnerable place, we seem to be wasting an awful lot.

Plastic pollution that quite literally embodies throwaway culture. Credit: Emilian Robert Vicol on Flickr